Article content

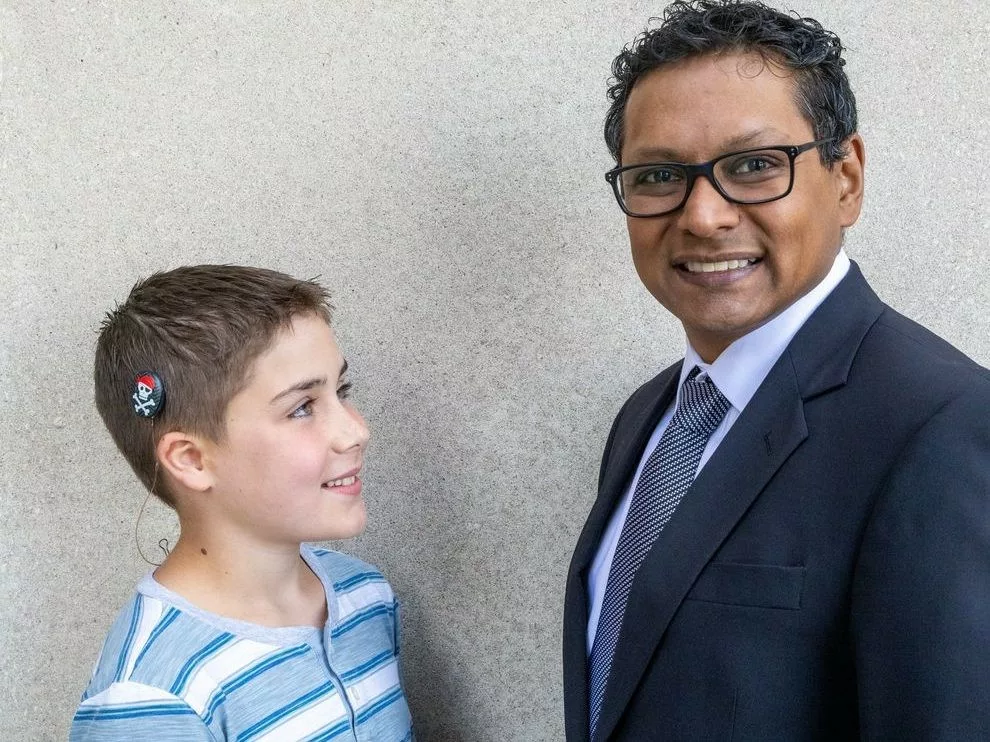

A young pioneer in Canadian implant surgery, 10-year-old Carter McDonald of London says one benefit is that he can now wear any hat or ball cap he wants.

That wasn’t the case before, when the Grade 4 pupil had to wear a special headband holding a device that helped him to hear.

McDonald’s parents have a different take on the life-changing surgery their son had at the London Health Sciences Centre (LHSC). Carter, born with a blocked canal in one ear, can now hear well and is a more confident youngster and doing better at school, they say.

Advertisement 2

Story continues below

Article content

“The day after the surgery, he comes home, and within hours, he feels better and wants to do everything, but we had to slow things down,” said Marzena McDonald, Carter’s mother. “Now, the TV doesn’t have to be turned up as loud, and he responds right away.”

Carter became the first person in Canada to receive the latest version of a special hearing aid implanted in the skull during an operation at LHSC, a pioneering procedure he had in 2020 and which the hospital shared Wednesday when it brought Carter, his seven-year-old sister and his parents back to help tell his story.

Carter was diagnosed as a newborn with atresia, a condition in which the ear canal lacks an opening. A regular hearing aid can’t help in such cases, and surgery to correct the condition was considered too risky, his parents and doctor said.

Carter’s parents were referred to LHSC and learned their son, then age seven, was a good candidate for the surgery to implant a thinner version of the hearing aid. He would become the first patient in the country to get it, replacing the headband he’d worn until then.

“Babies wear the headbands that vibrate their skulls so they can hear, but as they get older that headband is hard to wear and it’s kind of unsightly to wear in school,” Dr. Sumit Agrawal, head of neck and head surgery at LHSC, said. “So they (parents) look for a more permanent solution.”

Article content

Advertisement 3

Story continues below

Article content

Carter’s parents weren’t interested in traditional solutions to their son’s hearing problem, such as a device that can be attached to the skull that creates vibrations from sounds. Those vibrations reach the inner ear, bypassing its canal, and the brain interprets them as sound. The parents didn’t like that the device protrudes through the skin and can cause possible infections.

After looking around Ontario for help, Carter’s parents were offered the so-called bonebridge implant at LHSC. It’s a device that’s surgically placed beneath the skin on the skull, along with a magnetic device on top of the skin that functions like a microphone and can be removed if needed, for example to go swimming or wear a helmet.

The first bonebridge implant in North America was done in an adult in 2013, but Agrawal said the device was too thick to use in children because of their thin skulls.

“When Carter came to me, it just happened to be the same time they were releasing the next version of the implant,” a thinner model designed for children, Agrawal said.

The 45-minute surgery consists of drilling a hole in the skull, and the device is implanted through a tiny incision up to the hairline.

Advertisement 4

Story continues below

Article content

Recommended from Editorial

The device sits inside the skull, fixed by two screws. The implant captures sounds picked up by the external microphone and converts them into the vibrations that help the patient to hear, said Agrawal.

Carter’s implant was turned on four weeks after the incision from his surgery healed. He started hearing clearly right away, without any long adjustment.

“The beauty of it is that this is designed for life, so we don’t have to change it as a skull grows; it still keeps working, so they’re extremely reliable,” Agrawal said.

Since Carter’s surgery, other children in London – including younger ones – have received the same implant, as have adults with thinner skulls.

“We know that he is safer, so he can hear the surrounding sound,” said Reid McDonald, Carter’s father. “School isn’t an issue any more, and it could have been, potentially. He’s participating more in class and his confidence is better.”

Carter, who attends St. George’s public school in Old North, said he’s more active now in school, both inside and outside the classroom.

“I start track and field tomorrow, and I’m really excited,” he said.

bbaleeiro@postmedia.com

Article content

Comments